Baby sign language: A guide for the science-minded parent

What is “baby sign language”? The term is a bit misleading, since it doesn’t refer to a genuine language. A true language has syntax, a grammatical structure. It has native speakers who converse fluently with each other.

American Sign Language (ASL) and British Sign Language (BSL) are examples of genuine languages. By contrast, baby sign language, also known as baby signing, usually refers to the act of communicating with babies using a modest number of symbolic gestures. Parents speak to their babies in the usual way – by voicing words – but they also make use of these signs. For instance, a mother might voice the question, “Do you want something to drink?” while making the visual sign for “drink.”

Is baby sign language the same as ASL? Or BSL?

No, for the reasons stated above. But caregivers who teach baby sign language often use signs borrowed or adapted from the ASL or BSL lexicons.

Does baby sign language work?

The short answer is yes. It works in the sense that babies can learn to interpret and use signs. As I note below, research suggests that some babies start paying attention to signs by the age of 4 months (Novack et al 2022). By 8-10 months, they start producing signs themselves, and that can be an rewarding experience for families. But it isn’t clear that teaching babies to sign gives them any special, long-term, developmental advantages.

What signs do babies learn?

It depends. In some families, parents take a “DIY” approach. They notice helpful gestures that arise naturally during conversation— iconic gestures that “act out” or resemble the things they stand for. With deliberate use of these iconic gestures — and patient repetition — their babies eventually learn to interpret these gestures as signs.

For instance, suppose you take your baby outside and find that it’s very cold. You begin talking to your baby about it, and find yourself behaving like a mime: When you say the word “cold” you act out an exaggerated shiver with your arms. If you repeat this experience multiple times, your baby may learn to regard shivering arms as a sign for “cold.” You have invented your own sign!

In the same way, your family might invent a number of additional signs — signs based on pantomiming certain actions, or representing other creatures or objects with hand movements (like holding your hands to the side of your head to depict a rabbit with long ears).

But there’s another, more standardized approach to baby sign language: teaching your baby a set of pre-existing signs from a chart, book, or video. As Lorraine Howard and Gwyneth Doherty-Sneddon (2014) note, such signs are often adapted from languages for the hearing impaired. And while some of these signs involve iconic gesturing, many others do not.

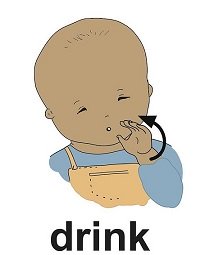

For example, consider the ASL sign for “drink.” As you can see from this illustration provided by Michael Fetters of the University of Michigan, the sign looks like you’re holding a cup to your mouth:

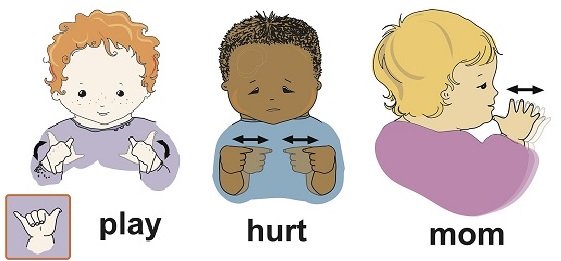

It’s very iconic. If you didn’t already know what this sign is supposed to mean, you could probably figure it out. But most ASL signs aren’t like this. The gestures don’t resemble the meaning in any obvious way. You can see what I mean in these illustrations of the ASL signs for “play”, “hurt”, and “mother” or “mommy”. The mapping of signs to meanings seems arbitrary, just as is the case for most spoken words.

Does it matter if a baby sign is iconic or arbitrary? Research suggests that it does. Babies tend to learn iconic signs more readily than arbitrary ones (Thompson et al 2012; Caselli and Pyers 2020).

Should you teach your baby signs? What are the benefits of baby sign language?

Teaching a baby to communicate using gestures can be exciting and fun. It’s an opportunity to watch your baby think and learn. The process might encourage you to pay closer attention to your baby’s attempts to communicate. It might help you appreciate the challenges your baby faces when trying to decipher language.

These are good things, and for some parents, they are reason enough to try baby signing. But what about other reasons — developmental reasons?

You’ll find many enthuastic claims online (Nelson et al 2012). Some advocates believe that baby signing programs have long-term cognitive benefits. They’ve speculated that babies taught to sign will amass larger spoken vocabularies, and even develop higher IQs.

Others have claimed that signing has important emotional benefits. They maintain that young babies may learn signs more easily than they learn spoken words, leading them to communicate more effectively at an earlier age. As a result, these infants end up experience less frustration and few temper tantrums.

Does the research support these claims? Not exactly. But it depends on what you mean by baby-signing. If you mean “teaching babies a few, arbitrary signs as a supplement to spoken language” then there’s no compelling evidence of long-term advantages. But if you’re thinking of the more spontaneous, pantomime use of gesture, that’s a different story. There is reason to think that easy-to-decipher, iconic gesturing can help babies learn. To see what I mean, let’s take a closer look at the research.

Do baby signing programs boost long-term cognitive skills?

Overall, the evidence is lacking. The very first studies hinted that baby sign language training could be at least somewhat advantageous, but only for a brief time period (Acredolo and Goodwyn 1988; Goodwyn et al 2000).

In these studies, Linda Acredolo and Susan Goodwyn instructed parents to use signs with their infants. Then the researchers tracked the children across 6 time points, up to the age of 36 months. When the children’s language skills were tested at each time point, the researchers found that babies taught signs were sometimes a bit more advanced than babies in a control group. For instance, the signing children seemed to possess larger receptive vocabularies. They recognized more words.

But the effect was weak, and detected only for a couple of time points during the middle of the study. For the last two time points, when babies were 30 months and 36 months old, there were no statistically significant differences between groups (Goodwyn et al 2000). In other words, there was no evidence that babies benefited in a lasting way.

And subsequent studies — using stringent controls — have also failed to find any long-term vocabulary advantage for babies taught to sign (Johnston et al 2005; Kirk et al 2012; Fitzpatrick et al 2014; Seal and DePaolis 2014).

For example, Elizabeth Kirk and her colleagues (2012) randomly assigned 20 mothers to supplement their speech with symbolic gestures of baby sign language. The babies were tracked from 8 months to 20 months of age, and showed no linguistic benefits compared to babies in a control group.

And what about IQ? Although some advocates have claimed that baby sign language training boosts a child’s IQ, the relevant research has yet to appear in any peer-reviewed journal. On this question, it’s safe to say that the jury is still out.

Does signing lead to better communication? Is it true that babies can sign before they can speak?

This is an interesting idea, and it’s been championed by advocates of baby signing programs. The proposal is that babies are capable of communicating via sign language months before they are ready to communicate with spoken language. Is there compelling scientific evidence for this claim? Once again, the answer is no.

The best evidence available on the question comes from a few, small studies of children raised to sign from birth. For example, two of the most relevant studies feature samples of fewer than a dozen children for a given age range. In these studies, the average timing of first signed words appears to be a bit earlier than the average timing observed for children learning spoken language.

But there is big problem. The sample sizes are just too small to draw any firm conclusions. For example, one long-term study (tracking the same babies from an early age) featured only 11 infants (Bonvillian et al 1983). Another study relies on data collected from only a few individuals each age group — for instance, just five individuals between the ages of 12 and 13 months (Anderson and Reilly 2002). When researchers rely on such small samples, we run a high risk of getting results that are skewed: It’s relatively easy to end up with a group of individuals who aren’t representative of the population as a whole.

And this is especially true when there is a lot of individual variation, as is the case for the timing of language production. For instance, at 13 months of age, it’s normal for some children to produce as few as 4 words, while others might produce many, many more. What if — by chance — your small sample includes mostly early bloomers? Or late bloomers?

Finally, there are methodological problems to be solved. We need to make sure we use similar standards when we count signs and spoken words, and different studies aren’t always comparable in this respect. So we still have a long way to go before we can answer this question. Read more about it in this Parenting Science article.

But surely there are situations where signing is easier than speaking?

I think that’s very likely. For example, the ASL sign for “spider” looks a lot like a spider. It’s iconic, which may make it easier for babies to decipher. And it might be easier for babies to produce the gesture than to speak the English word, “spider,” which includes tricky elements, like the blended consonant “sp.” The same might be said for the ASL signs for “elephant” and “deer.”

But most ASL signs aren’t iconic, and, as I explain here, some gestures can be pretty difficult for babies to reproduce — just as some spoken words can be difficult to pronounce. So it’s unlikely that a baby is going to find one mode of communication (signing or speaking) easier across the board.

And the social and emotional benefits? Is there evidence that baby signing reduces frustration or stress?

Individual families might experience benefits. But without controlled studies, it’s hard to know if it’s really learning to sign that makes the difference. To date, claims about stress aren’t well-supported. One study found that parents enrolled in a signing course felt less stressed afterwards, but this study didn’t measure parents’ stress levels before the study began, so we can’t draw conclusions (Góngora and Farkas 2009).

Nevertheless, there are hints that signing may help some parents become more attuned to what their babies are thinking.

In the study led by Elizabeth Kirk, the researchers found that mothers who had been instructed to use baby signs behaved differently than mothers in the control group. The signing mothers tended to be more responsive to their babies’ nonverbal cues, and they were more likely to encourage independent exploration (Kirk et al 2012).

So perhaps baby signing encourages parents to pay extra attention when they communicate. Because they are consciously trying to teach signs, they are more likely to scrutinize their babies’ nonverbal signals.

As a result, some parents might become better baby “mind-readers” than they might otherwise have been, and that’s a good thing. Being tuned into your baby’s thoughts and feelings helps your baby learn faster.

But of course parents don’t need to participate in a baby sign language program to achieve these effects. The important thing is tuning into your baby, and figuring out what he or she wants. And this begs the question: Does teaching your baby signs (from ASL or other languages) necessarily give you more insight into what your baby wants?

Families can communicate quite successfully without using formal “baby signs”

For example, consider the sign for “more,” borrowed from ASL. You bring your fingers and thumb together on each hand, and then tap your hands together by the fingertips. It’s a perfectly useful sign, and many babies have learned it. But what happens if you don’t teach your baby this sign?

Will your baby be incapable of letting you know that he wants more applesauce? Will your baby somehow fail to get across the message that she wants to play another round of peek-a-boo?

When parents pay attention to their babies — and engage them in conversation, one-on-one — they learn to read their babies’ cues. A baby might pat the table when he wants more applesauce. A baby might reach out and smile when she wants to play with you. They aren’t signs borrowed from a language like ASL, but, in context, their meaning is clear. When we respond appropriately to these spontaneous gestures, we are engaged in successful communication, and we are helping our babies build the social skills they need to master language.

That doesn’t mean there is no reason to teach formal signs. You might find that some signs are helpful — that they allow for communication that is otherwise difficult for your baby. But it’s wrong to think of formal signs as the only gestures that matter. From the very beginnings of humanity, parents and babies have communicated by gesture. And research suggests that gestures matter. A lot!

In fact, this is so important, it’s worth considering in more detail. Whether or not you decide to teach your baby sign language, you should embrace the use of gestures when you communicate.

Why everyday gestures can have a big impact on your baby’s development

Our nonverbal cues can help babies learn language

Imagine I stranded you in the middle of a remote, isolated nation. You don’t speak the local language, and the locals don’t recognize any of your words. What would you do? Very quickly, you’d resort to pantomime. And as you tried to learn the language, you’d soon appreciate that some people are a lot more helpful than others.

It isn’t just that they’re friendlier. Some people just seem to have a better knack for non-verbal cues. They follow your gaze, and comment on what you’re looking at. They point at the things they are talking about. They use their hands and facial expressions to act out some of the things they are trying to say. And they’re really good at it. When they talk, it’s easier to figure out what they mean.

Researchers call this ability “referential transparency,” and it helps babies as well as adults. The evidence? Erica Cartmill and her colleagues (2013) made video recordings of real-life conversations between 50 parents and their infants – first when the babies were 14 months old, and again when they are 18 months old. Then, for each parent-child pair, the researchers selected brief vignettes – verbal interactions where the parent was using a concrete noun (like the word “ball”).

The researchers muted the soundtrack of each vignette, and inserted a beeping noise every time the parent uttered the target word. Next, they showed the resulting video clips to more than 200 adult volunteers. They asked the volunteers to guess what the parents were talking about. When you hear the beep, what word do you think the parent is saying?

The researchers were pretty tough graders. They didn’t, for example, count guesses as correct if they were too general (like guessing “toy” when the correct answer was “teddy bear”). Nor did they give volunteers credit for guesses that were too specific (guessing “finger” when the correct answer was “hand”). They also tried to eliminate vignettes where it was possible for volunteers to read the parents’ lips.

So the test wasn’t easy, and it might give us an idea of how challenging it is for babies to decipher unfamiliar words. The outcome? It turns out there was a lot of variation between parents. Some parents spoke with referential transparency only 5% of the time. Others were more like expert foreign language teachers, making their meanings clear up to 38% of the time.

And — here’s the part with implications for the long-term — there were links between a parent’s referential transparency score and her child’s vocabulary three years later. Babies who had more “transparent” parents tested with larger vocabularies when they were four and half years old.

The link remained significant even after controlling for the babies’ vocabularies at the beginning of the study. And there were other interesting points too. Although the sheer number of works spoken by parents predicted a child’s vocabulary, it was high-quality, transparent communication that mattered most. And while researchers replicated a well-known finding – that parents of higher socioeconomic status (SES) use more words with their kids – there were no links between SES and referential transparency. Parents of high SES were no more likely than other parents to speak to their babies in a highly transparent way.

What do we make of these results? We can’t be sure that referential transparency caused larger vocabularies. Maybe parents who scored high on referential transparency did so because they possessed a heritable trait – one they passed on to their kids – that makes people both better communicators and better verbal learners.

But remember: Parents with high referential transparency were easier for adult volunteers to understand, and these adults were unrelated to the parents. So it isn’t hard to imagine how referential transparency could lead to long-term language gains. And other research suggests that we can help our babies by being responsive to our babies’ spontaneous gestures. For example, consider the importance of pointing.

Babies learn words faster when we label the things they point at

Most babies begin pointing between 9 and 12 months, and this can mark a major breakthrough in communication. By pointing, babies can make requests (e.g., “Give me that toy”). They can also ask questions (“What is that?”) and make comments (“Look at that!”).

But the impact of this communicative breakthrough depends on our own behavior. Are we paying attention? Do we respond appropriately? As psychologists Jana Iverson and Susan Goldin-Meadow have noted, a baby who points at a new object might prompt her parent to label and describe the object. If the parent responds this way, the baby gets information at just the right moment—when she is curious and attentive. And that could have big implications for learning (Iverson and Goldin-Meadow 2005).

Experiments have confirmed the effect: Babies are quicker to learn the name of an object if they initiate a “lesson” by pointing. And if the adult tries to initiate — by labeling an object that the baby didn’t point at? Then there is no special learning effect (Lucca et al 2018).

So there’s good reason to think that gestures affect learning. But the trick is to emphasize easy-to-decipher gestures.

We want to be like that those language tutors in the remote, far-off country – the ones who respond to other people’s requests for information, and who have a knack for supplementing speech with easy-to-understand pantomime.

Does this mean that abstract, non-iconic signs pose a problem? Can baby sign language delay speech development?

That’s a reasonable question, given that baby signing programs feature signs that are non-iconic. Could the difficulty of learning such signs be a roadblock?

Studies haven’t found that babies trained to use signs suffer any disadvantages. So if you and your baby enjoy learning and using signs, you shouldn’t worry that you’re putting your baby at risk for a speech delay. In essence, you’re just teaching your baby extra vocabulary — vocabulary borrowed from a second language.

Still, it’s helpful to remember that iconic gestures are easier for your baby to figure out. For example, in one experimental study, 15-month-old toddlers were relatively quick to learn the name of a new object when the adults gestured in an illustrative, pantomime-like way. The toddlers were less likely to learn the name for an object when the spoken word was paired with an arbitrary (non-representational) gesture (Puccini and Liszkowski 2012).

What’s the takeaway?

Non-verbal communication is crucial for language development. Gestures can provide babies with important information, and help them decipher your meaning. But not all gestures are equally helpful. Research suggests that the most effective approach is

- to pay attention to our babies, and respond appropriately to their spontaneous attempts to gesture and verbalize; and

- to communicate with babies using a combination of speech and transparent getures — like pantomime and pointing.

In addition, I suspect it’s beneficial to build on those signs and gestures that you and your baby spontaneously invent. They already have meaning to your baby, and they are probably easier for your baby to remember.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t also teach your baby sign language, including some arbitrary, non-iconic signs. It can be fun and interesting, and your child might end up learning signs that are very useful. But to help your baby learn, it makes sense to emphasize gestures that are easy to decipher, and which have personal meaning to your baby.

Tips for teaching baby sign language

Whether you opt for the spontaneous, do-it-yourself approach, or you want to teach your baby gestures derived from real sign languages, keep the following tips in mind.

How early can you start introducing your baby to signs? As early as you like, but remember that it will take time for your baby to learn how to make signs.

Babies with developmentally normal hearing begin learning about language from the very beginning. They overhear their mothers’ voices in the womb, and they are capable of recognizing their mother’s native language – distinguishing it from a foreign language – at birth. Over the following months, their brains sort through all the language they encounter, and they start to crack the code. And by the time they are 6 months old, babies show an understanding of many everyday words – like “mama,” “bottle,” and “nose.”

Many babies this age are also beginning to babble – repeating speech syllables like “ma ma ma” and “ba ba ba.” If a 6-month-old baby says “ba ba” after you give her a bottle, could it be that she’s trying to say the word “bottle”? If an infant sees his mother and says “mama,” is he calling her by name? It’s possible. And as noted above, research suggests that many babies are speaking their first words by the age of 10 months. (Read more about it in my article, “When do babies speak their first words?”)

So we might expect that babies are ready to observe and learn about signs at an early age — even before they are 6 months old. In support of this idea, a recent experimental study found evidence that babies as young as 4 months paid close attention to a signing adult. They watched as a native user of ASL signed to them, and looked back and forth between her signs and the object she was discussing (Novack et al 2022). Does this mean that 4 month old babies are ready to produce signs themselves? No. But it suggests we can help them learn about the meaning of signs, and that is a crucial part of language development.

Introduce signs naturally, as a part of everyday conversation.

Babies learn words and signs by being repeatedly exposed to them, and by using them in real conversations. So let your signs come up naturally, and avoid turning these episodes into parent-driven lessons. Remember the experiments about pointing. Babies learn when they’re the ones who initiate.

Keep in mind that it’s normal for babies to be less than competent. Don’t pretend you can’t understand your baby just because his or her signs don’t match the model!

Just a baby’s first attempt to say “bottle” falls short (“ba ba,”) his or her early attempts to gesture will likely be less than perfect. Baby sign language instructors call these attempts “sign approximations,” and they recommend that you run with them. In some cases, your baby might lack the fine motor skills to form the correct version of the sign.

Pretending that your baby didn’t really communicate effectively to you — because your baby’s gesture isn’t exactly what you want — is counterproductive. Don’t forget: Babies develop better language skills when their parents are tuned in and helpful!

More reading

You can read more about the timing of signing and speaking in this article. I review the evidence, and address misconceptions about baby sign language.

For more information about communicating with babies, see my review of fascinating research about the effects of eye contact on infants. It discusses how shared gaze primes your baby’s brain for communication and language-learning.

In addition, see this Parenting Science article about how certain aspects of infant-directed speech help babies learn language.

Interested in gesture? You should be! Research suggests that gesture does more than help babies learn language. It can also help kids grasp mathematical concepts, and more. Read about it in my article, “The Science of gestures.”

References: Baby sign language

Acredolo, LP and Goodwyn SW. 1988. Symbolic gesturing in normal infants. Child Development 59: 450-466.

Acredolo L and Goodwyn S. 1998. Baby Signs. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Anderson D and Reilly J. 2002. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Normative data for American Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 7: 83–106

Bonvillian JD, Orlansky MD, Novack LL. 1983. Developmental milestones: sign language acquisition and motor development. Child Dev. 54(6):1435-45.

Cartmill EA, Armstrong BF 3rd, Gleitman LR, Goldin-Meadow S, Medina TN, Trueswell JC. 2013. Quality of early parent input predicts child vocabulary 3 years later. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(28):11278-83.

Crais E, Douglas DD, and Campbell CC. 2004. The intersection of the development of gestures and intentionality. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 47(3):678-94.

Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ. 1994. Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 59(5):1-173.

Fitzpatrick EM, Thibert J, Grandpierre V, and Johnston JC. 2014. How handy are baby signs? A systematic review of the impact of gestural communication on typically developing, hearing infants under the age of 36 months. First Language. 34 (6): 486–509.

Goodwyn SW, Acredolo LP, and Brown C. 2000. Impact of symbolic gesturing on early language development. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 24: 81-103.

Howard L and Doherty-Sneddon G. 2014. How HANDy are baby signs? A commentary on a systematic review of the impact of gestural communication on typically developing, hearing infants under the age of 36 months. First Language 34(6):510-515

Iverson JM and Goldin-Meadow S. 2005. Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological Science 16(5): 367-371.

Iverson, J.M., Capirci, O., Volterra, V., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (in press). Learning to talk in a gesture-rich world: Early communication of Italian vs. American children. First Language.

Johnston JC, Durieux-Smith A and Bloom K. 2005. Teaching gestural signs to infants to advance child development: A review of the evidence. First Language 25(2): 235-251.

Kirk E, Howlett N, Pine KJ, Fletcher BC. 2013. To Sign or Not to Sign? The Impact of Encouraging Infants to Gesture on Infant Language and Maternal Mind-Mindedness. Child Dev. 84(2):574-90.

Lucca K and Wilbourn MP. 2018. Communicating to Learn: Infants’ Pointing Gestures Result in Optimal Learning. Child Dev. 89(3):941-960.

Mayor J and Plunkett K. 2011. A statistical estimate of infant and toddler vocabulary size from CDI analysis. Developmental Science 14(4): 769-85.

Meins E, Fernyhough C, Fradley E, and Tuckey M. 2001. Rethinking maternal sensitivity: Mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Discipline 42: 637-648.

Meyer RP. 2016. Sign language acquisition. Oxford Handbooks Online. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.19.

Nelson LH, White KR, and Grewe J. 2012. Evidence for website claims about the benefits of teaching sign language to infants and toddlers with normal hearing. Infant and Child Development 21(5): 474-502.

Novack MA, Chan D, and Waxman S. 2022. I See What You Are Saying: Hearing Infants’ Visual Attention and Social Engagement in Response to Spoken and Sign Language. Front Psychol. 13:896049.

Oller DK. 2000. The emergence of the speech capacity. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Petitto LA. 1988. “Language” in the prelinguistic child. In F. S. Kessel (ed.), The development of language and language researchers: Essays in honor of Roger Brown (pp. 187–221). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Petitto LA and Marentette PF. 1991. Babbling in the manual mode: Evidence for the ontogeny of language. Science 251: 1493-1496.

Puccini D and Liszkowski U. 2012. 15-Month-Old Infants Fast Map Words but Not Representational Gestures of Multimodal Labels. Front Psychol. 2012;3:101. Epub 2012 Apr 3.

Seal BC and DePaolis RA. 2014. Manual Activity and Onset of First Words in Babies Exposed and Not Exposed to Baby Signing. Sign Language Studies 14(4): 444-465.

Thompson R, Vinson DP, Woll B, and Vigliocco G. 2012. The road to language learning is iconic: Evidence from British Sign Language. Psychological Science 23: 1443–1448

image of mother holding gesturing infant by fizkes / shutterstock

image of baby girl clapping cropped from photo by istock / TakakoWatanabe

image of baby sitting on father’s lap by Drazen Zigic / shutterstock

Drawings of baby signs are © 2012 Regents of the University of Michigan. They appear courtesy Dr. Michael Fetters (PDF hereopens PDF file ), and are shared via the Creative Commons license BY-SA

Portions of this text derive from earlier, published versions of the article, written by the same author (Gwen Dewar). In addition, some of the sentences about Cartmill’s study originally appeared in blog post written by Gwen Dewar for BabyCenter.

Content last modified 8/2022